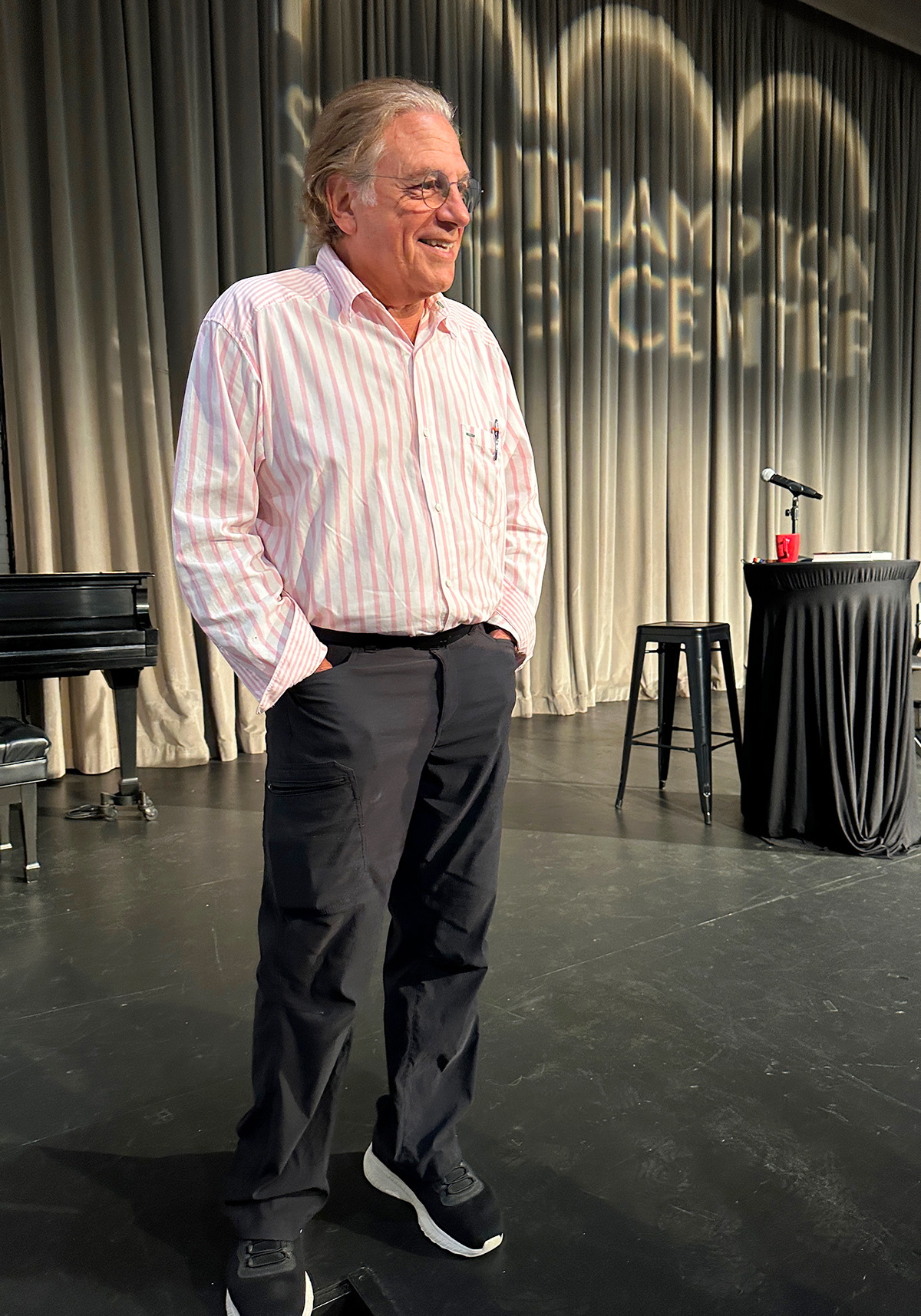

Gerald Rosengarten in Talks with Julia Szabo: The Power of Design to Shape Minds and Cities

History’s most influential and innovative business leaders all have one thing in common: they appreciate the power of great design to change people’s minds, and thereby the world. Author and entrepreneur Gerald (Jerry) Rosengarten’s long and remarkably varied career proves the point. In fact, entrepreneur almost doesn’t do justice to what Rosengarten is really all about.

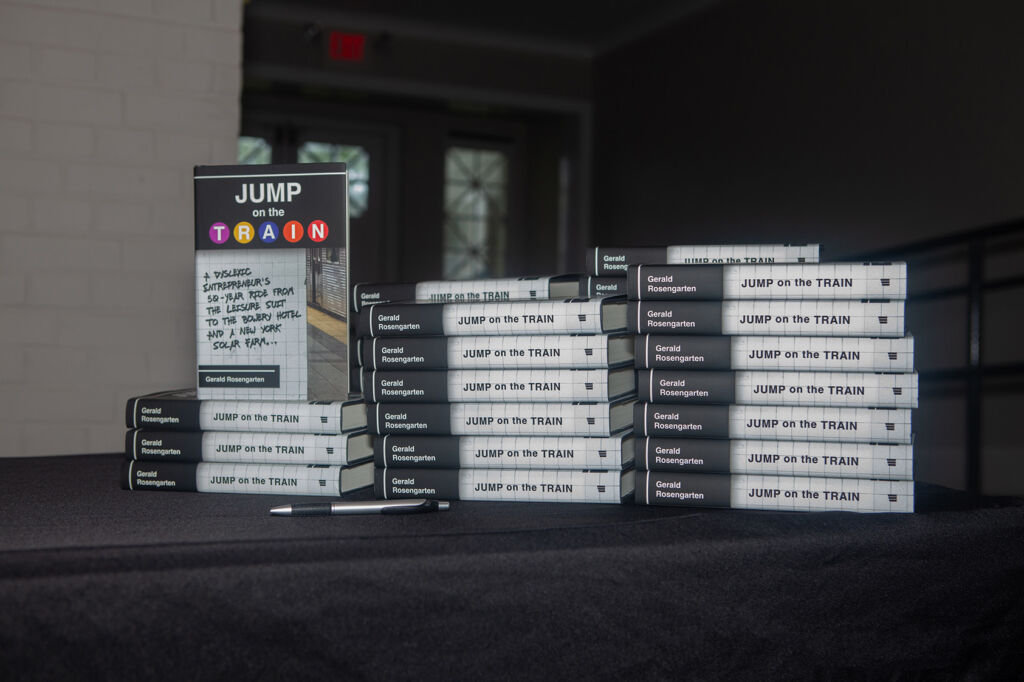

"If you ask me to describe what I am," he writes in his new book, Jump on The Train, "I will say I am a designer. I thoroughly enjoy it, and it's the thing I do best, although not necessarily to everyone's taste."

Ever since bravely overcoming dyslexia in his teens, when the condition was not yet widely understood, Rosengarten has displayed a tenacity and gift for the creative work-around that won’t quit to this day. This self-avowed “nonconformist businessman” initially burst on the business scene in the 1970s, when he singlehandedly invented two iconic milestones of swinging seventies menswear — the polyester leisure suit and patchwork denim — leaving an indelible mark on the fashion and marketing worlds in the process. Although he would quit the fashion world soon after rocking it to its core, Rosengarten never stopped designing.

"For me, design is my reading," he explains. "Just as reading is a learning tool, so is design. Without the ability to read, I have always looked at life differently; I view it from a design standpoint. Design," he adds, "is bringing ideas to life. Steve Jobs… Elon Musk… Steven Spielberg... these are people who appreciate and realize great design. The architect Peter Marino is an exceptional designer, and a great example of someone I would say has the same type of vision that I have. He understands that design makes money, yes -- and it also empowers people."

A Drizzler?

For Rosengarten, it was a logical segue from fashion -- what people live and work in -- to real estate: designing and marketing the spaces and places where we live and work. Nowadays, dedicated medical properties increasingly populate what Rosengarten calls "the NYC universe of real estate development." But back in 1984, the idea of a destination for doctors that wasn't a hospital was far ahead of its time. That's the year Rosengarten envisioned and created the Greenwich Medical Arts Building, designed specifically to house medical practitioners' offices. The project ended up being so successful, it prompted Rosengarten to coin a now-favorite term: he called the building a "'Drizzler,' because it would keep spitting out cash flow."

Today, the term “Soho Loft” is synonymous with a chic, spacious lifestyle. This wasn’t always the case on the wild frontier South of Houston Street, where intrepid artists occupied cavernous, cold-water loft spaces illegally. With impressive out-of-the-box thinking, Rosengarten invented legal loft living, foreseeing the tremendous potential of those no-frills studio work spaces as world-class luxury residential units with all modern conveniences.

A few blocks East, on lower First Avenue, steps from Alphabet City’s notorious squatter phenomenon, an experimental platform for edgy actors, directors, and playwrights was in danger of losing its home, a beloved cultural anchor for its creative community. The plight of Theater for the New City (TNC) spoke poignantly to Rosengarten, whose love of acting had motivated him to learn his lines by running them over and over again, until he had them successfully memorized. (After playing leading roles on his high school stage, he studied method acting at the Actors Studio, storied stomping ground of immortals ranging from Marlon Brando to Marilyn Monroe, James Baldwin to Lorraine Hansberry.)

In a nail-biting scenario worthy of a screenplay, Rosengarten swooped in and saved TNC. His ingenious renovation plan dared to envision the Lower East Side as a residential neighborhood equal in chic to the redoubtable Upper East Side. With suitably dramatic flair, Rosengarten capped the theater with a prestige residential building. And the tenants came from near and far to pioneer a hip new neighborhood, whose hipness factor has only grown in the ensuing decades.

The Bowery Hotel

Rosengarten followed that achievement with another daring venture: re-imagining The Bowery on Manhattan's Lower East Side. Once the definition of an undesirable location, a magnet for alcoholic indigents, the formerly low-life lower Third Avenue transformed into an unlikely, yet very real, destination for high rollers in 2007, when Rosengarten opened the doors of his now-fabled Bowery Hotel. The "paparazzi playground" quickly became a happening haunt for the rich, famous, and infamous. Another down-at-heels neighborhood re-designed as a well-heeled one; another NYC real-estate frontier, conquered.

This brilliant real-estate career would eventually culminate in not one, but two labors of love: the solar farm Rosengarten designed on Long Island (Middle Island Solar Farm), inspired by a similar one he admired on a tour of Italy’s Puglia region; and the sustainable Southampton green home he designed, built and still lives in with his wife, Paula. But that’s not the end of his story, for he has more projects still in the works, including one he’s particularly excited about. Encircling the periphery of his solar farm is an oval pathway. Always designing and re-designing spaces, Rosengarten envisions that pathway as a running track.

Once completed, it will host an event he's proudly in the process of establishing: "Run for The Sun," turning the solar farm into "an athletic arena for our society's most vulnerable: high school students of all learning abilities. Absolutely anyone can compete -- track and field experience not required! Scholarships and Apple products will be awarded to the winners. My goal is to uplift high school students, because they are our country's future, and the world's."

If all goes according to plan, the winning runners might also receive the cool watchband Rosengarten recently designed, “to keep Apple Watch wearers from getting uncomfortably hot and sweaty while doing sports.” He, his wife, and a few of their close friends are already wearing the first watchband prototypes. “It’s a home run if Apple takes it,” says the inventor, with a smile.

Rosengarten relates profoundly to high school students, particularly those coping with cognitive challenges. Through all of his entrepreneurial adventures, as he fearlessly faced down challenge after challenge, only one thing paralyzed him with fear: the printed page, his Kryptonite. Words would leap around on the pages of books, leaving him defeated, while teachers and schoolmates cruelly mocked his disability; sadly, this was decades before today’s disability empowerment. Dyslexic for as long as he can remember, Rosengarten diligently faced down his inability to read, getting by with assistance from his now-deceased brother Howard (to whom Jump on The Train is fondly dedicated). Now, however, it’s evident to both the author and his readers that the reading challenge impacting some 40 million Americans needn’t hold anyone back, from anything. In fact, it’s something of a superpower.

"You can't even imagine what it's like to not be able to read," Rosengarten says. "Most of my life, I had to learn from people as opposed to books." Writing and publishing a book of his own wasn't just empowering for Rosengarten; he'd like it to motivate as many others as possible. "My book is designed to open up the fact that you don't have to just succumb to a problem," he says. "You can get over the problem. There are so many different ways to do things! I enjoy inventing change," he adds. "I'm a real estate developer who drives change." Dyslexia may well have been the ultimate entrepreneurial blessing in disguise. Because of his reading challenge, Rosengarten concludes, "I would see what wasn't there more than what was there, and I'd make it happen. It's like I'm always proving something, always going further."

See what isn’t there, make it happen, go further: This is what designers do. All in a life’s work for Jerry Rosengarten.

-Julia Szabo